www.bangkokpost.com, 29 January 2010

http://www.bangkokpost.com/entertainment/movie/31955/give-peace-achance

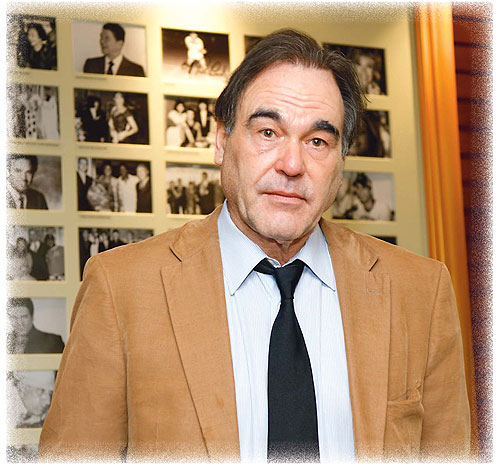

On his brief visit to Bangkok earlier this week, Oliver Stone laid out his narrative of peace through the evocation of war. He talked about the dark clouds smothering the world, the forces of history and conformism, the way young people are crippled by amnesia, the post-9/11 lynch mob hysteria, the prejudices of the US news media, the self-delusion of superpowers. The US director also talked about Avatar, and about the virtues and vices of movies, at least smart movies that want to say something to the world.

To achieve peace in this dark time, he said, we must show that we really need it. ''We need the collective will to do it. [We have to show] the sweaty toil of 'needing' something _ and not just 'wanting' it.''

A Vietnam War vet and filmmaker whose political outspokenness has earned him flowers and flak over the past 30 years, Mr Stone was in Bangkok as a guest of the Vienna-based International Peace Foundation, an independent institution that has arranged a series of talks and activities by prominent figures on the theme of ''Bridges: Dialogues Towards a Culture of Peace.''

On Monday Mr Stone spoke at the New International School of Bangkok, then at the packed Foreign Correspondents' Club. He flew to Phnom Penh on Tuesday, where the next leg of the programme took place. It was a rather short visit by a personality who seems to know this country well _ since his days fighting in Indochina and when he arrived here to shoot Alexander in 2004.

Many Thai viewers know Mr Stone from that historical epic in which Colin Farrell played the homosexual ruler and which included clamorous battle scenes starring Thai actors and elephants. The film was a flop, yet it added to Mr Stone's repertoire of movies that explore outsized, troubled, controversial figures, a theme that seems to characterise his career. After winning Oscars for best director for Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July, Mr Stone made the sizzling, counter-myth JFK, the brooding Nixon, The Doors (about the life of Jim Morrison), Commandante (consisting solely of the director interviewing Fidel Castro), W. (about the life of George W Bush), and, as recently as last September, he released the documentary South of the Border, in which he interviewed Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez.

''They're different, these personalities. Nixon is very different from Jim Morrison and Bush Jr. is the opposite of Alexander. That's because I'm interested in different types of people,'' he said.

To observers, though, these figures at least share a similarity in the way that they can be both regarded as either great rulers or radical tyrants. ''Strong leaders are necessary, but yes, sometimes they do harm,'' Mr Stone said.

''Alexander did some harm. But I always argue that the good that he did far outbalanced the bad things. Then [look at] Castro; he created a revolution and we [the US government] tried to kill him right away. America behaves as if Castro is a demon and a despot, but his human rights behaviour is nothing comparable to the American behaviour _ the way we throw people in prison. Compared to other Latin American leaders, Castro's record is pretty good. But no one is perfect.''

Talking about Latin America allowed Mr Stone to mince no harsh words against the US's involvement in the region; he mentioned the ''disgusting, unjust double standard'' _ a buzzword here, also _ that his government applies to different nations in Central and South America. This firebrand attitude, which charges his films with raw power, is also the cause of the criticism lashed out at him by those who hold a different view, who like to bundle him up with Michael Moore, another outspoken filmmaker, as mudslingers and nuisances.

Mr Stone believes, however, that the news media in the US, especially the television networks, have become profit-seeking organisations instead of being a public service that provides fair and thoughtful information to the people. ''News shouldn't be making money,'' he said. ''Television has stopped what at least the print media is still doing _ to probe a little further.''

Because of this, he believes that films, especially documentary films, should play a bigger role. ''Documentary has a gigantic role to play,'' he said. ''But the problem is they don't get much distribution. With the Internet, we do get more out. [Someone like] Michael Moore makes a difference with his movies. But documentaries are not really watched. People still want stories and action and escapism. If you have a man and a gun on a poster, it always works. I think it's the same in Bangkok, too.''

In his speech at the FCCT, Mr Stone praised the movie-of-the-moment, Avatar, for its ability to subconsciously influence viewers to want to save the world. In an interview with Real.Time, the director elaborated on the point of how movies can function as a valve in the world where violence and aggression are prevalent _ and the complexity of the fact that movies thrive precisely on selling violence and war.

''Films can absorb violence,'' he said. ''You can have Mel Gibson shooting people, or you can have Avatar, with its technological warfare. People like it, because it's a form of release. The smart filmmakers can find the way, like Cameron did in Avatar, to channel the aggression and to express a purpose and a message, as opposed to just being silly.

''Look at the films that will be nominated for the Oscar this year,'' he continued. ''We have The Hurt Locker [about a bomb squad in Iraq], which is realistic, but it doesn't take any real position; it's a smart film that shows us about the addiction of war, but it's very apolitical. Whereas actually Avatar is a little more political. Then we have Up in the Air, and Precious [both dramas]. And Inglourious Basterds [the World War II film by Quentin Tarantino]. Look, three out of five top films are about war. America loves war.

''But like I said, good filmmakers know how to differentiate. Film can absorb violence; a lot of the aggression can be put through film, as it can do through art, or music.''

It's not only America that loves war and aggression, Mr Stone half-joked, and added that the Thais may indeed enjoy the same passion. Mr Stone is known to be a staunch champion of the 2001 Thai film Bang Rajan, a blood-soaked historical film about a band of patriotic Ayutthaya villagers who die fighting the Burmese army. The director bought the Thai film for US release, and he confirmed his view again that Bang Rajan is a great film, ''up there with Seven Samurai.''

Upon learning that Thanit Jitnukul, the director of Bang Rajan, is planning a sequel, Mr Stone joked: ''But how many villagers were left alive at the end [of the first film]? You'll keep fighting the Burmese?''

We may have to, cinematically. For Mr Stone, however, his next film will be about a different kind of aggression; to him, it's an old scourge that has recently assumed a new force. Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps will be the director's sequel to his 1987 film starring Michael Douglas as a rogue stock trader. ''Twenty years after the original film, Wall Street is getting more serious, the numbers are bigger, the computers faster, more dangerous,'' he said. ''Now you can tip the whole market with no rhyme or reason, and we're talking billions of dollars, not millions. What happened was that the recent crisis was like a major heart attack.

''A film with a message about greed and money worship,'' he said, ''is more urgent than ever.''

|